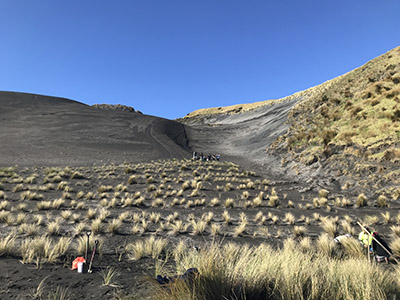

Coastcare Waikato and volunteers on site at Ngārahae Bay.

As the saying goes, drastic times call for drastic measures.

A pest plant is being called upon to help stabilise a large scale “difficult site” on the west coast between Awakino and Marokopa.

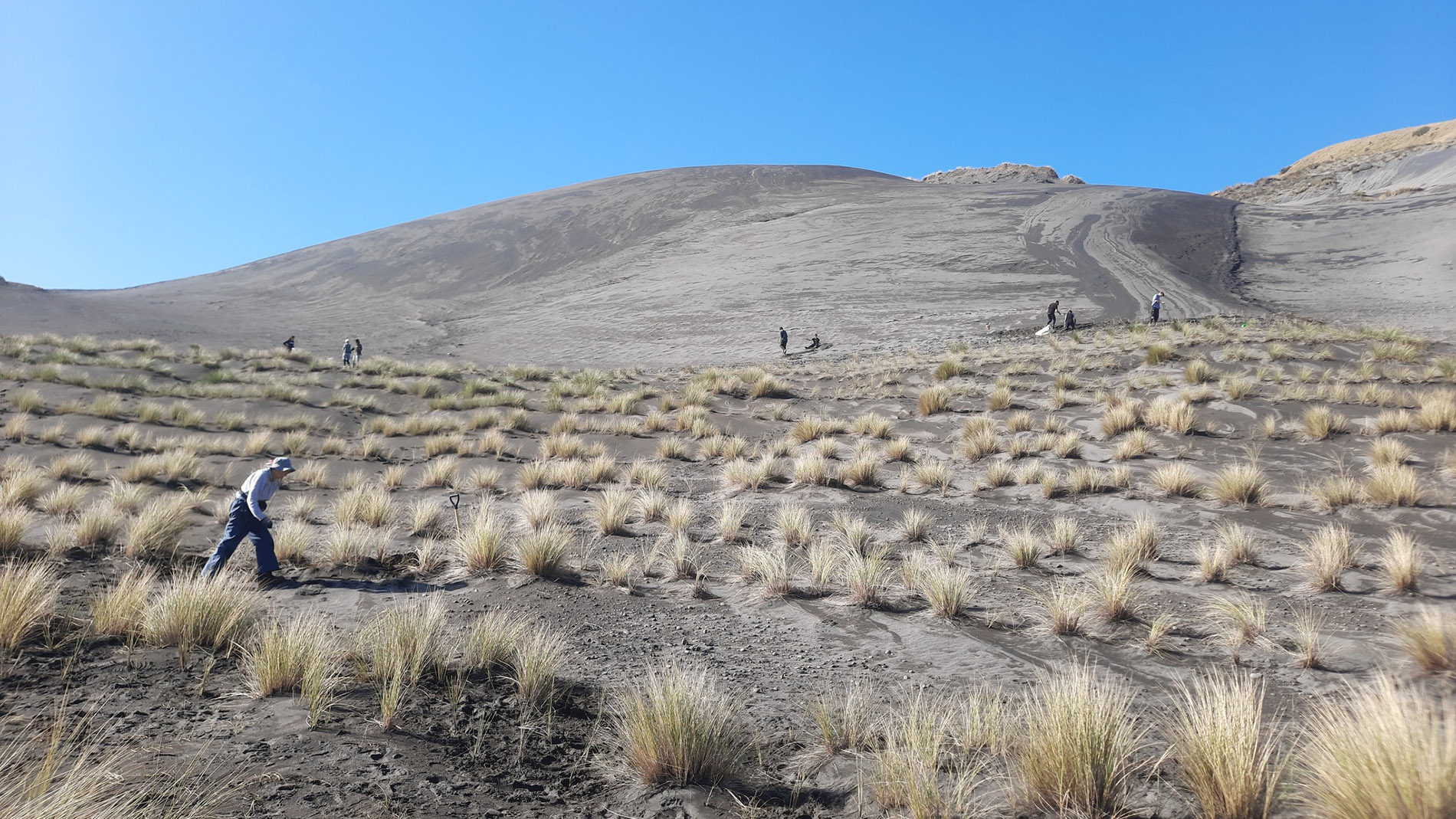

More than 8500 marram grasses have been planted into a large dune at Ngārahae Bay as part of a partnership project between Waikato Regional Council, the Coastal Restoration Trust and landowners Nukuhakari Station.

Coastcare Waikato West Coast Co-ordinator Stacey Hill says while marram isn’t commonly used in restoration practices anymore, because it can outcompete native grasses, the exotic plant is strategically being used as a temporary solution to stabilise the dune before coastal native shrub and forest species can be planted.

“Drastic times call for drastic measures. The end goal is for the area to be established as a coastal native forest, but first we need to stabilise the loose sand to make the environment suitable for our native trees and shrubs as they will not take hold in bare sand,” says Stacey. “Rather than sacrificing precious spinifex as an initial stabiliser, we’re planting marram grass instead and have a comprehensive plan to manage it out.”

The dune, known as a ‘difficult', has been steadily migrating inland for over 150 years.

The dunes at Ngārahae Bay have steadily been migrating inland for over 150 years, due to historic land use practices (which saw the removal of stabilising native vegetation) and severe westerly winds. The dunes cover an area of over 8 hectares, including hundreds of metres of pasture.

“The scale of this site is incredible,” says Stacey. “In the past, this would not have been a natural dune.”

The project began in 2013. The first job was to re-establish a frontal dune as that had completely blown away, leaving behind exposed coffee rock.

Stacey says this involved planting a good width of kōwhangatara/spinifex and pīngao in the seaward edge of the large mobile dune, which has stopped further movement of sand inland. The plants are trapping wind-blown sand in a natural dune system so the problem is no longer getting bigger.

“This was a really important part of the project,” says Stacey. “Our coasts naturally erode and build up in cycles of erosion and accretion. But if we’re losing sand from the coastal system, such as what was happening here with the sand being lost inland, then there will be less natural accretion along our coastlines.”

Work is now focused on stabilising the landward bare dune to eventually restore native shrubland and forest.

The rows of marram will hold sand and create swales between them, into which native shrubs and trees will then be planted.

“The idea is that the rows of marram we’re planting in the back dune will hold the sand and create swales between them, into which we'll then plant the native shrubs and trees.

“Eventually the marram will die out, due to being shaded out by the larger natives, or be sprayed.”

To date, about 32,000 native plants, including kōwhangatara, wīwī, pōhuehue, harakeke, toetoe, oleria, tauhinu, akeake, ngaio, taupata and karo, have been planted as part of the project.

“The vision is to this slope covered in native forest, one that supports thriving populations of native insect, lizard and bird life.”

To ask for help or report a problem, contact us

Tell us how we can improve the information on this page. (optional)